Article

Antarctic ice-shelf meltwater outflows in satellite radar imagery: ground-truthing and basal channel observations

Jakob S. Hamann, Thomas Arney, James D. Kirkham, Paul Wachter, and Karsten Gohl

Journal of Glaciology vol. 70 () pp. 366 DOI: 10.1017/jog.2024.71

Abstract

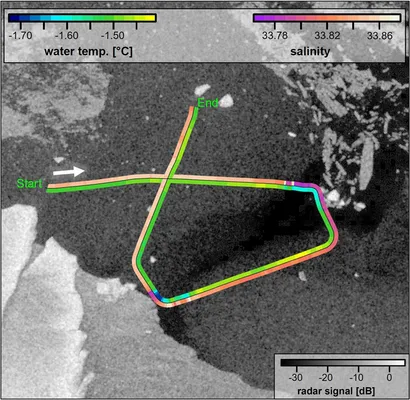

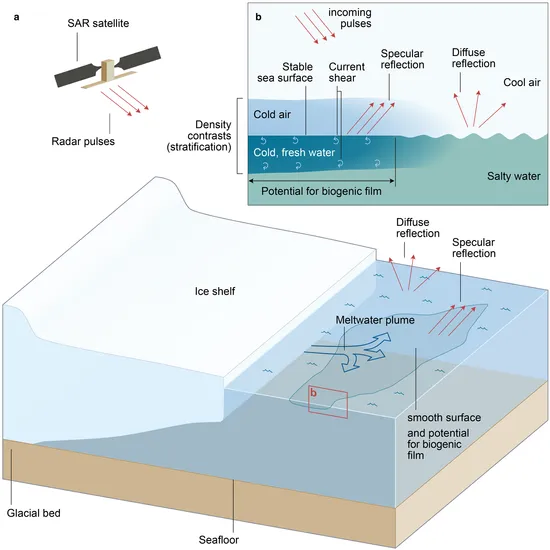

Ice shelves regulate the flow of the Antarctic ice sheet toward the ocean and its contribution to sea-level rise. Accurately monitoring the basal and surface melting of ice shelves is therefore essential for predicting the ice sheet’s response to climatic warming. In this study, we utilize Sentinel-1A synthetic aperture radar satellite imagery combined with shipboard measurements of water temperature and salinity to investigate the presence of surficial meltwater plumes along the Antarctic coastline. Our approach reveals a strong correlation between areas of pronounced low radar backscatter extending from ice shelves and significant decreases in water temperature and salinity, suggesting meltwater-enriched ocean waters. We propose that the low radar backscatter signature of meltwater outflows is caused by stable stratification of the upper water column, driven by density contrasts from buoyant, low-salinity meltwater and surface current shear that reduce Bragg scattering waves. The resulting smooth water surfaces were observed adjacent to the surface expression of deep basal channels, documented in a helicopter survey along part of the Bellingshausen Sea ice edge. We present high-temporal resolution satellite radar as a tool for identifying meltwater release from beneath ice shelves, capable of all-weather, day-and-night imaging.

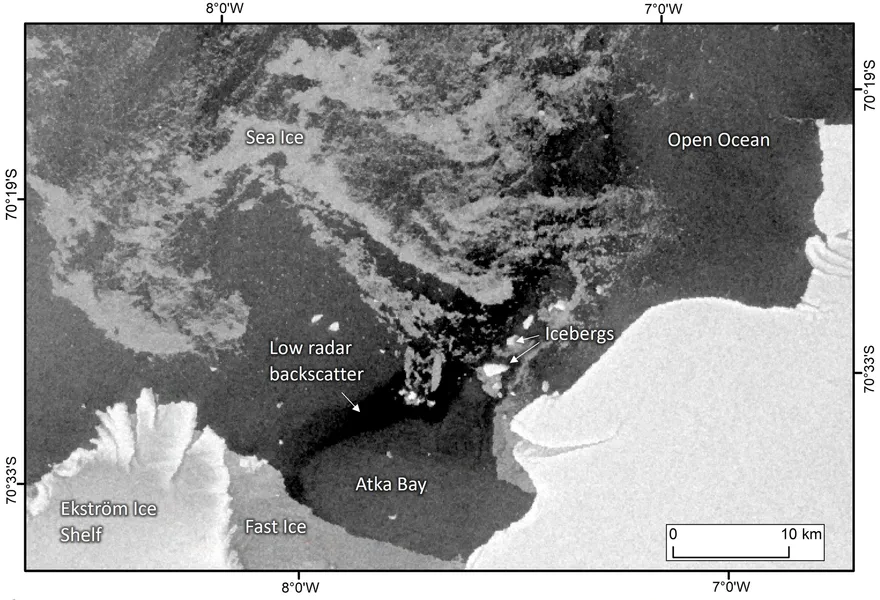

While on a research expedition in 2022 to East Antarctica, we noticed an unusual dark area in one of the regular satellite radar images we use to monitor sea ice conditions:

Comparing it to measurements taken as the ship passed through the area confirmed the water in the patch was colder and fresher, indicating meltwater from the nearby Ekström Ice Shelf flowing out into Atka Bay.

A second example happened almost exactly a year later on another expedition to West Antarctica, near the George VI Ice Shelf.

That expedition also gave us a clue about the mechanism behind the effect. Some ice shelves have long depressions caused by channelised melting from below. On Venable Ice shelf, they were about a kilometre wide, 30—40 m deep, and stretching from the ice edge nearly 40 km inland.

They also often had glossy patches of water just in front of them, much smoother than the surrounding water. They were offset from the ice edge, so it wasn’t just because they were sheltered from the cold winds coming off the ice sheet.

Since the basal channels they were in front of are formed by meltwater, it’s likely that these patches are where that (less dense) meltwater is surfacing. We suspect it’s a similar effect that’s causing the larger scale dark patches in the radar image.

The way the radar pulses bounce off the sea affects how many get back to the satellite. In a rough sea, they get reflected all over the place, and some make it back. The flat patches of meltwater act like a mirror, and the pulses all get reflected away in the same direction — away from the satellite, making a darker image.

Being able to monitor melting ice shelves using satellite radar imagery could be extremely useful, since it’s unaffected by weather, works whether it’s light or not, and (as with all remote sensing), is always-on, covers huge areas, and doesn’t require expensive expeditions to remote areas. However, this technique does need more validation with in situ measurements of the water temperature and salinity at more sites to be confident of its effectiveness.

If confirmed as a reliable technique, it could be developed into an unsupervised monitoring system of ice shelf melting, adding data to a vital topic in our warming world.