Southern lights, magic sparkledust, and Capt. Hand-towel

This is part of a series of letters I sent home during my first research expedition, on the German icebreaker Polarstern.

You can start at the beginning here.

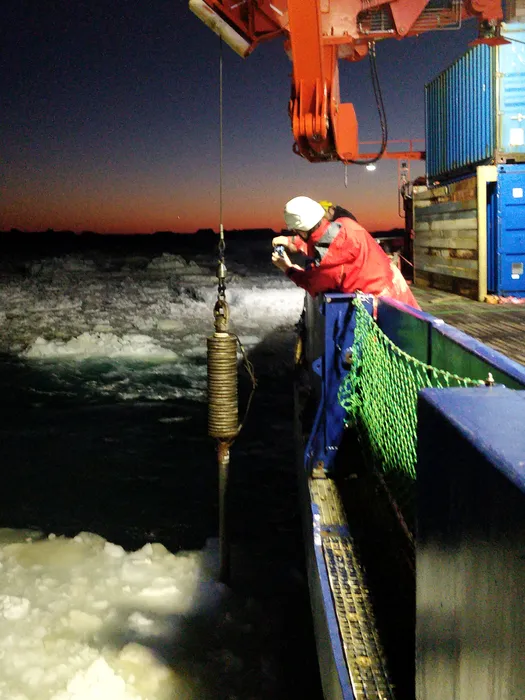

After our second visit to Molodezhnaya, we worked at a few stations to the east of Cape Ann, making up for the ones we’d had to miss because of the big storm. These were some of the most picturesque places we’ve worked at yet. One of them required us to enter “iceberg alley” in front of the Australian Mawson station. As we approached through thick sea ice, at twilight and shrouded by a strange fog, we passed seals and colonies of Adélie penguins perched on pressure ridges and capsized icebergs. At one point we were heading straight for a group of nine of them, who were not in the least bit bothered by twelve thousand tonnes of steel icebreaker bearing down on them. The lookout shouted “Springt, Jungs!” (“Jump, boys!”) at them as they disappeared from view under our bows, but luckily they appeared again a few seconds later down our starboard side, running and sliding away. At this station, we had to push the sea ice sideways to open up enough water to get our gravity corer in, and hope that none of the sea ice caused any problems with it.

After that station, we moved northwest and the sea surface got less interesting, but it was made up for by the sky — Cape Ann is one of the few places where the Antarctic mainland juts out north of the Antarctic Circle, and so we were treated to darkness, though still only four hours or so of twilight. Because of this, every now and then the southern polar lights danced in the skies above us as we worked. In fact, on our penultimate station we had the full moon just rising on one horizon, the dim twilight glow of the sun which set a few hours ago on the other, between them, Venus was rising, and above us, the polar lights were shimmering in front of the Southern Cross and the Milky Way. The crew switched off the deck lights for a bit so we could all enjoy the view. For a while, the lights were just nebulous wisps quite far away, but at one point they appeared right over us, a real curtain of vertical green rays waving back and forth slowly.

This was also the last station at which the oceanographers took measurements and samples with their CTD rosette: every now and then they’ve been sending down this instrument to collect data about the conductivity, temperature, and pressure (depth) from the whole water column, and then collect up to 24 samples in big 20-litre “bottles”. Tradition dictates that on the last CTD cast of any cruise, two of these big bottles are filled with alcohol and sent into the abyss, then drunk upon its return. We did it with Campari and orange juice, which for reasons long forgotten has become the drink of choice on this expedition. Unfortunately, the journey down and back managed to completely separate the Campari and the orange juice (the oceanographers were actually quite excited by this apparent density stratification), so the first glass tapped from the bottle was pure Campari. After dismounting and vigorously shaking the bottle (which required two people), the drink was satisfactory and was dispensed to the waiting crowd. The rest of that bottle plus the other one ended up in Zillertal the next night, strapped to the wall and open to anyone.

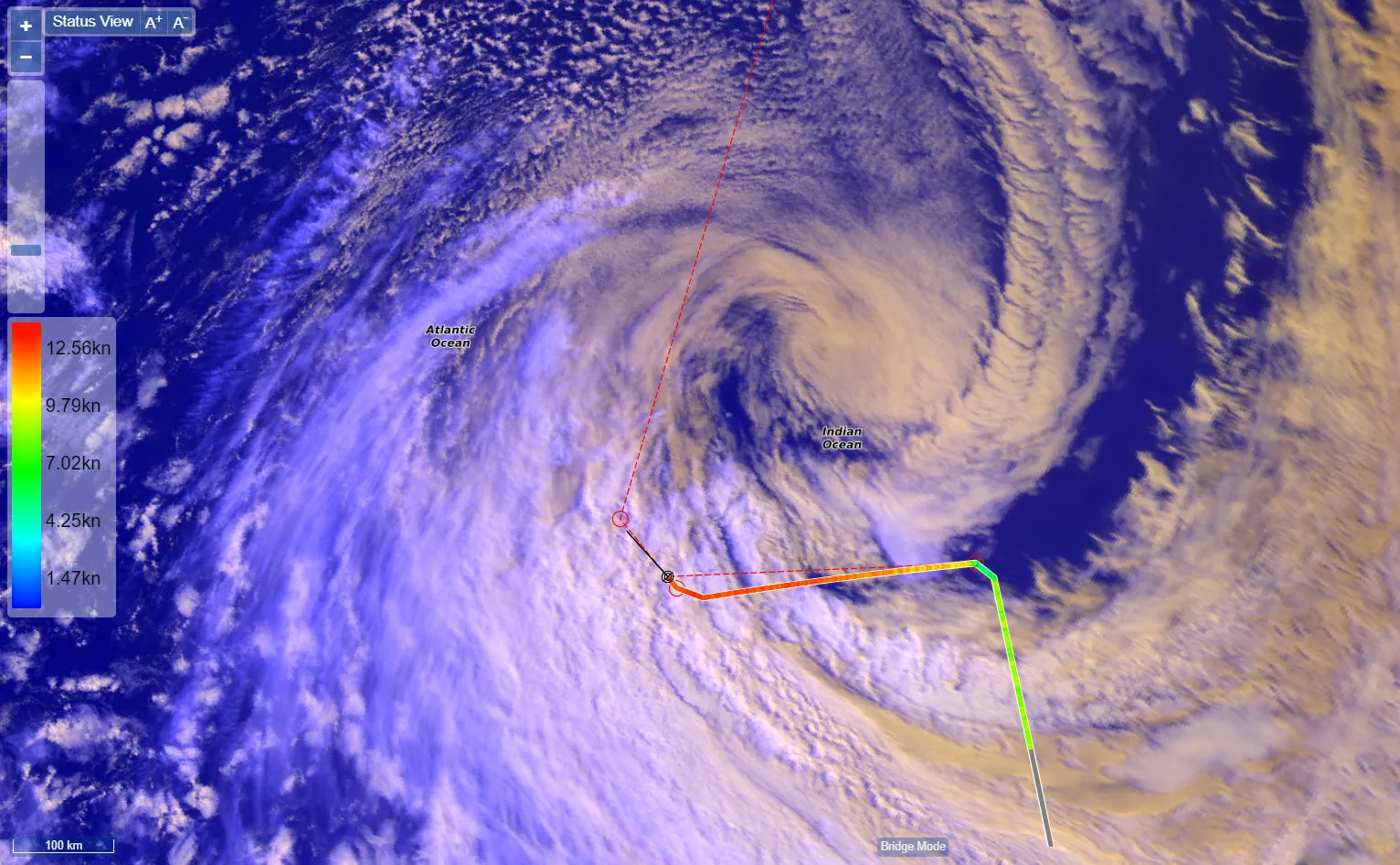

After these stations, we started our long transit back to Cape Town: 2600 nautical miles northwest, with our last station halfway at the Atlantic-Indian mid-ocean ridge. Unfortunately, the geology work at this last station was cancelled after we encountered another storm which made work on deck unsafe, and we then diverted around it to avoid the worst. The satellite image of the storm with our track superimposed shows what a good idea that was.

Since then, we’ve slowly been getting longer and darker nights, with warmer and warmer weather — in fact at this point it’s colder below decks than outside, which is very strange after months of the outside being well below freezing. We left the polar lights behind long ago, but the dark nights have revealed another wonder of nature to us: bioluminescence. As we pushed northwards through the waters of the Agulhas Current, we could see sparks of fluorescent green in our wake as we disturbed the organisms living in the surface waters (dinoflagellates, probably). The effect was transfixing and at the same time almost comical: we were literally leaving a trail of green sparks behind us, looking a lot like we were being powered along by a stream of magic sparkling dust. Every now and then a much larger and continuously glowing patch would appear, seemingly quite deep. If the glowing sea wasn’t enough, the sky was also awash with billions of stars: the darkest skies of all are at sea, and if you found an area of the ship’s decks that wasn’t brightly lit (the helipad was best), you could spend all night looking at the span of the Milky Way, complete with dark patches of interstellar dust, at the Southern Cross, Alpha Centauri, Canopus, Orion (still upside-down) and two nebulae which I wasn’t able to identify. At one point I saw a long string of bright dots just above the southern horizon heading from west to east: my guess was this was the very early stages of a launch of yet more Starlink satellites by Elon Musk.

During the day, or when it was cloudy at night or there were no dinoflagellates swimming around us, the transit was not the most interesting part of the expedition. Luckily, I’d gained my sea legs and I was largely unaffected by the large swells we experienced most of the way home, but they did make me feel drowsy, and the effort you have to expend balancing yourself or staggering around the decks (the classic “seaman’s gait”) only adds to the tiredness. The only things we had to do were clean everything (enough to pass a “white glove” inspection by the chief mate) and write the cruise report.

I think everybody was feeling the ten days of transit stretching out before us, so everyone found things to do: the evening lecture series restarted with enthusiasm (I did a surprisingly well-received talk about maritime and Antarctic flags yesterday), the helicopter crew and ship’s engineers ran tours of their respective domains, and there were many, many evenings of drinking and partying. One of them was a formal affair in the Blue Saloon — very much the state room on board, bedecked in flags and containing the library. This was the only time anyone ever used it, and we all had to dress up for the occasion — officers in their dress uniforms, the rest of us in the least creased, most recently washed t-shirts we could find. It was a farewell, both to everyone at the end of the cruise and to three of the crew who were retiring: two sailors and the first mate. All of them started in the seventies and had varied careers in merchant shipping, ending up on Polarstern. The captain was particularly sad to be saying goodbye to his first officer, who had in fact turned down the captaincy and stayed as first mate, not wanting all the extra paperwork. That had left the way free for Moritz to become Polarstern’s captain, and the seventh in a long line of fathers and sons in the family to be sea captains.

The last Zillertal was run by the helicopter crew (calling themselves the Heli Mafia…), on the same evening. While it was “dress fancy” upstairs, it was fancy dress downstairs, because Karneval was happening in Germany (particularly Cologne — or would have been, if it hadn’t been cancelled there because of the war in Ukraine). Announcing a fancy dress party with less than a day’s notice and on a ship with very few resources and limited wardrobes all round made it a challenge and a lot of Romans wearing bedsheet togas resulted, but there were some surprisingly good efforts: a penguin (a black changing robe and white and yellow paper), two bats (bin bags, wire, tape), Minnie Mouse (a sacrificed red towel), a queen (tin foil and a foil survival blanket as a cape), and a monk (with a blatantly pre-meditated cossack and rosary). There were also those who had tried their best but had fallen slightly short of the mark, and I must include myself (and Matt) in this group: we came as diatoms (I came as Fragilariopsis kerguelensis, he came as F. curta) by hanging a big piece of paper down our fronts, cut into the right outlines and with the diagnostic features drawn on. Mine at least was sort of 3D, since I folded some bits to represent the ribs, but overall they were weak and extremely nerdy costumes. Still, we weren’t the worst: others (who shall remain nameless) came as a “fairy” (wearing their shower curtain with “fairy” written on their forehead), as a ski instructor (simply by wearing their normal outrageous tracksuit), and as a basketball player (again, by wearing the same vest and cap they wore the majority of the time anyway). Then there were two who are difficult to put in either category: one covered himself in rubbish and came as the great Pacific garbage patch, and another used all the (many) towels he’d never handed back to the laundry and came as “Kapitän Handtuche” (Captain Towel). Both were probably the stars of the show.

Unfortunately, this left the last barbeque without its theme, a fact that my shift leader (and a wonderful man) was quite annoyed about. He had wanted to make the barbeque not just a fancy dress party, but an actual Karneval celebration. With everyone having spent their energies on the Zillertal evening though, nobody wanted to dress up again, so the Karneval theme ended up being reduced to just his speech, the Büttenrede: a traditionally funny satirical poke at authority. He did a great job at making fun of everybody on board and was even organised enough to hand out an English translation of his speech in advance.

The barbecue itself (the third of the trip) was excellent: like Polarstern’s 40th birthday one, we all communally grilled our own ostrich and kudu, but this time we could stay out on deck in the sun, and then go and watch the magic sparkling waters as night fell. We all watched the sunset very closely: some on board were adamant that they’d seen a green flash at sunset before; others didn’t believe them. Our onboard offline Wikipedia seems to corroborate the green flashers, but sadly no flash was observed that evening.

Anyway, we’ve finally cleared customs, health checks, and inspections, and we’ve got our passports back: we’re free to explore Cape Town for just over a day, before our flights back to Europe. This is the end we all knew was coming but couldn’t believe would actually arrive! Many new friends and 115 GB of photos on the shared drive to remember it by though.