Surviving a Southern Ocean storm

This is part of a series of letters I sent home during my first research expedition, on the German icebreaker Polarstern.

You can start at the beginning here.

Just after my last letter our meteorologist showed us a big low atmospheric pressure area bearing down on us, and forecast a heavy storm likely to last three or four days. Not everybody believed him, but it seemed hard to argue with the synoptic chart, which showed this low taking up half of the Southern Ocean, and us very near its projected centre. We prepared as best we could by going around our labs and cabins lashing down anything that could move and stuffing cupboards and drawers with anything that couldn’t be tied down. The crew emptied the swimming pool, bolted deadlights over the portholes, and reinforced the big doors to the wet lab with steel girders, amongst many other precautions.

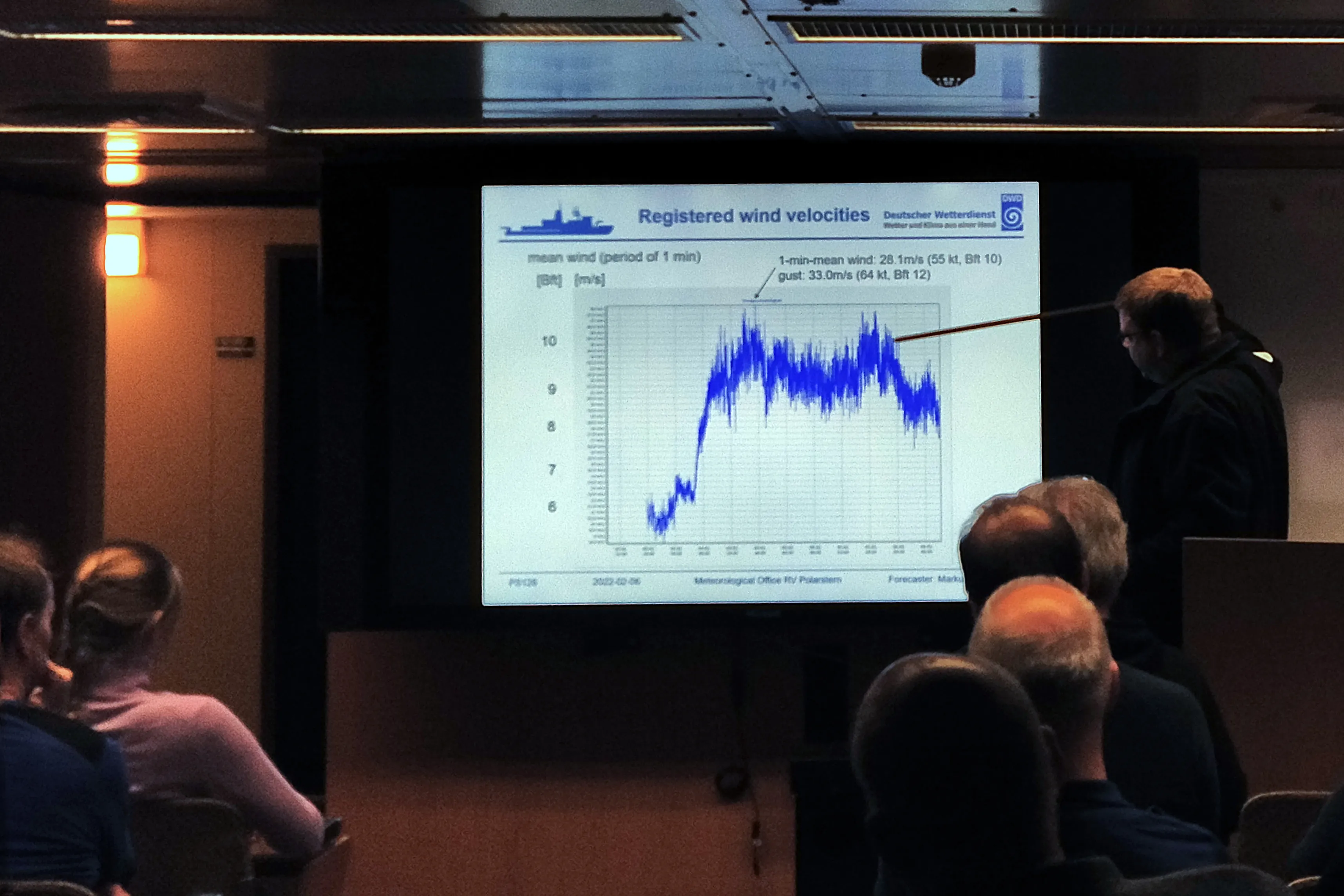

When it came, it came quickly. We were pitched into eight to ten-metre waves (picture the highest diving board in the Olympics) and high storm-force winds (55 kn; 100 kph) with “hurricane-force” gusts (64 kn; 120 kph). The working deck was closed, and then pretty soon afterwards we were banned from going out on any deck. The ship was pitching and rolling 20 degrees one way and then the other, and sending everything flying, despite our efforts at tying things down. Objects we really hadn’t expected to move were sliding around or falling over, doors were banging because the magnets supposed to hold them open weren’t strong enough, and it was impossible to walk around the ship without crashing into walls or objects as you suddenly went from pushing up quite a steep hill to staggering downhill or being thrown sideways. My one-month-old sea legs were put to the test and found wobbling. The sensation was uncomfortably like being extremely drunk. Apparently.

My seasickness pills were out of their depth: I think they’re more suited for Auntie Doris who can’t sit in the back of the car than a raging storm in the “screaming sixties” of the Southern Ocean. They helped — they stopped me from actually throwing up — but they weren’t strong enough to let me go about my normal business (not that anyone was doing much). The only refuge I had was my bed — lying flat with my eyes closed and head still magically stopped all nausea. Unfortunately, that meant I spent the majority of three or four days in my cabin, emerging cautiously for bread and water every now and then. Spotify chose this moment to delete all my downloaded music, and I couldn’t look at anything so films and books were out too. That left me with outdated back episodes of podcasts to keep me entertained until Matt (completely unaffected, damn his eyes) revealed he had many audiobooks downloaded, and thereby saved the day.

Yesterday, the storm blew itself out (though much less rapidly than it came) and we got back down to a force 7 (“Near Gale”) which my tender sea legs could just about cope with. I managed to eat properly (more than just an apple with peanut butter per day), and the sea state was just about calm enough to allow work to continue (though it still felt pretty risky).

I’m not sure where, on the spectrum of what one could expect on an expedition, this storm would sit — I think a cruise without a fairly significant storm would be unusual, but the damage that the storm had inflicted upon poor old Polarstern does seem to make this one a little more violent than usual: some of the ten-metre waves we’d experienced had broken over our stern, where Polarstern has a ramp from the wooden-planked deck down to the water, guarded by a pair of heavy steel gates. The waves had both ripped up a whole section of wooden planking to reveal the steel deck below, and sheared one of the steel gates almost entirely in half, near its hinges. There had also been a section of steel coring pipe lashed to the deck which had broken free and got itself wedged between the deck and the guardrail, a trolley jack had been flying about the deck, and we’d lost both buoys used to float the seismic team’s airguns. The coring pipe alone takes three strong people to lift it.

Apart from a couple of unfair comments about the British supposedly being seafaring people, everyone was pleased to see me and concerned for my health when I finally did emerge from my cabin. In the few failed attempts to either experience the storm on the bridge or try and turn up to our shift meetings, I’d met very few people — largely I think because most people were feeling it one way or another. I was amongst the most affected, but I don’t think the worst.

It turns out to have been very wise to have tested the lifeboats in the idyllic bay a week ago, and similarly wise to stow the lifeboats just over ten metres above sea level. Luckily — or rather thanks to the skill of the captain and crew — we didn’t need them. And I often felt reassured that if anything did happen, we weren’t completely alone down here: the Chinese icebreaker was also weathering the storm with us somewhere out there, and either ship would have absolutely risked everything to come to the assistance of the other, whatever our respective governments might think of each other.