A day in the life of an Antarctic marine geologist

This is part of a series of letters I sent home during my first research expedition, on the German icebreaker Polarstern.

You can start at the beginning here.

We’ve finished our work in the first working area near Neumayer station on the very eastern edge of the Weddell Sea, and we’re now transiting through the Lazarev and Riiser-Larsen Seas to the Cosmonauts Sea, where we will drop off our land team. Then we continue east to the Cooperation Sea, near the Australian Mawson Station, our second major working area. In all, the transit between our working areas is about 3500 km, longer than the entire Eastern Seaboard of the US.

The transit has been a more relaxing time than the full-on 4 pm ‒ 4 am 12-hour shifts in our first working area (and soon to be the case again in our second working area), but it’s still been a little topsy-turvy. For one thing, we’re still on our shift patterns, but finishing at midnight, not 4 am. That leaves me in the slightly odd position of having free time from midnight to 4 am when few others are awake, and when nearly thirty years of training say I should probably be heading to bed. If I do I can’t sleep, since midnight is the equivalent of about 7 pm. Happily, the Germans are doing their best to fill those hours for me, usually with beer. If it’s not just a Feierabendbier (their special word for after-work beers), then it’s a full-on party.

We celebrated Polarstern’s 40th birthday (40 years since her naming ceremony) the other day with a BBQ on deck. I don’t know if it’s the German way or just the Polarstern way, but we all got the salads and meat we wanted from a buffet then went to the big BBQs and grilled our own meat — it meant you had to keep an eye on the right piece of ostrich or kudu (a perk of leaving from Cape Town), or someone else would mistake it for theirs. It was fun eating with the sea ice floating by, but when it got too cold, we went inside to another part of the working deck which had been decked in flags and coloured lights and tables, benches, and a (free) bar installed. The Captain gave a speech about the ship and ended by saying he hoped very much that when the end of her work with AWI came in a few years, she would still be used somehow, or at the very least preserved in the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven. I think everyone agreed, she’s a fun ship to be on and she’s looking after us well. Then the tables were cleared away, and the “no photos after 10 pm” rule came into effect.

The transit has also given us time to enjoy our pool and sauna, in the bows on the lowest deck (excluding the engine rooms), right where the ice hits when we’re icebreaking. That means you can hear and feel the grinding, smashing noises of the freezing sea ice hitting the steel of the hull while you’re relaxing in the lovely hot wood-panelled sauna. When we’re breaking through particularly thick sea ice, we often end up rolling just as much as we were with a big swell on the open ocean, since the method is to just ram the ice and we often bounce and slide off it. The difference is that a swell is relatively predictable and what goes left must go right. When we’re beached on an ice floe the roll can sometimes just stay there for what seems like forever, until the ice cracks or we slide off it. These are the times when swimming in the pool is particularly exciting. The pool is actually rarely used for swimming: it has basketball hoops at either end, and we mostly use it to play a cross between water polo and basketball which is a lot of fun.

It won’t be long now though until we have to stop this relaxing and socialising and get back to the difficult work. After we’ve transferred our land geology team to the Russian Molodezhnaya station, we’ll head on for two weeks of similar work to the first working area: typically, 12 hours of cold, wet, heavy lifting, ending at 4 am.

Let me try and give some more details about a typical work day: usually, I try and wake up by noon — seven hours’ sleep, and just in time for the end of lunch according to the crazy meal times on board. So far I’ve found it hard to be excited about veal or chilli con carne for breakfast, so I either try my luck at getting the vegetarian option (I didn’t sign up as a veggie), or I skip lunch altogether and wait until the mess is empty and scrounge some bread and Nutella with some fruit.

Then I have a few hours of free time, during which I might write one of these emails, go to the gym, or just go on deck and spot penguins and seals or watch us icebreaking. At the end of my free time, and just before my shift, we have “Kaffeezeit”, when some kind of cake is served up for an afternoon snack.

On every other day at 4 pm, there’s a general science meeting in the cinema/conference room, in which the chief scientist updates everyone on the science work we’ve done in the last day or two and the plan for the next few days. Then it’s down to the main deck and our shift meeting to discuss what needs to be done today. All our work is based around “stations”: one location where the ship stops, uses its various thrusters to keep position, and then we operate one or more pieces of kit.

For us marine geologists on board, the gravity corer is our workhorse because it’s simple and gets relatively long samples relatively reliably. It works by just pushing a long steel tube into the mud with a 1.5-tonne weight on top and then pulling it out. That’s it.

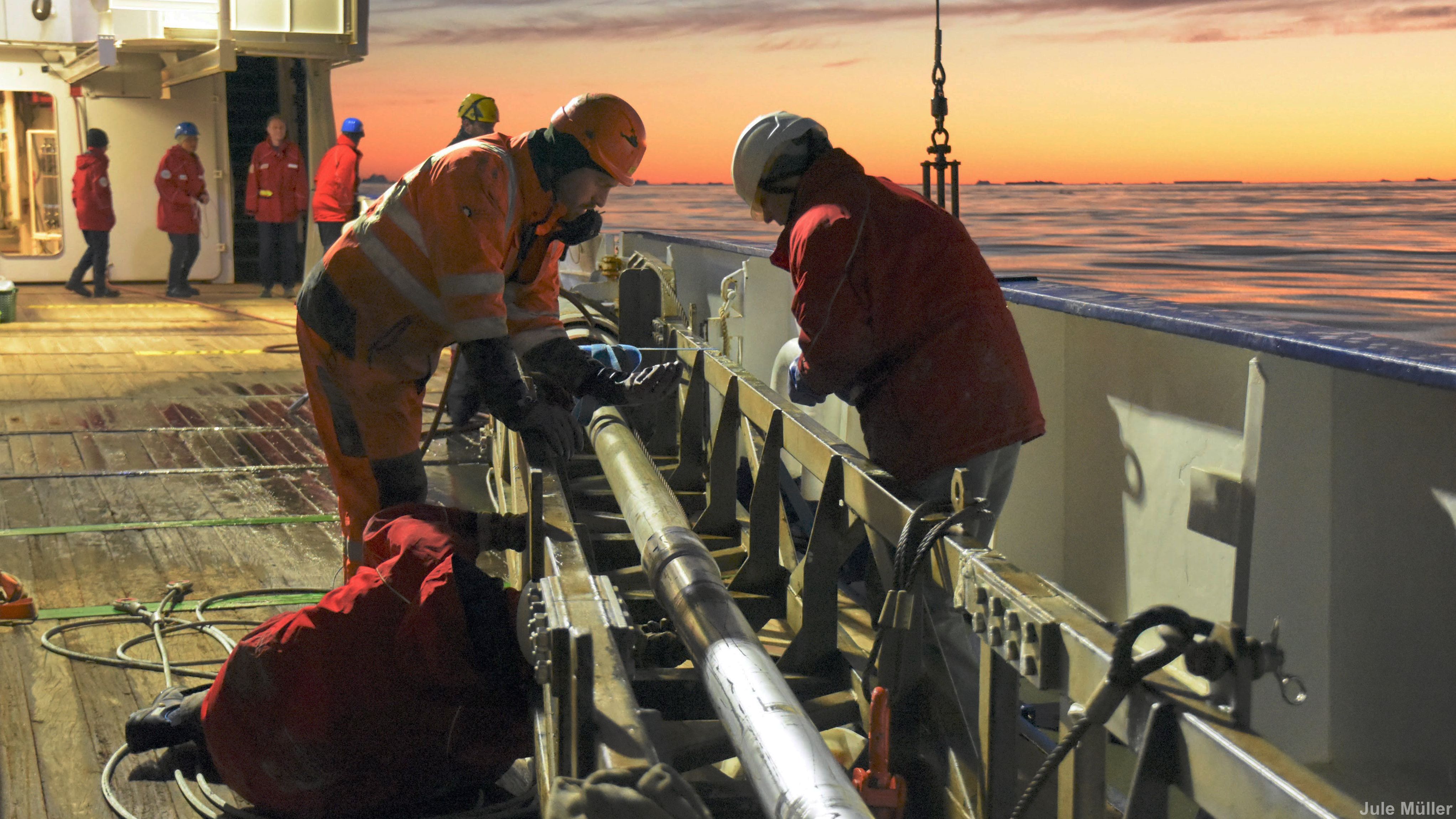

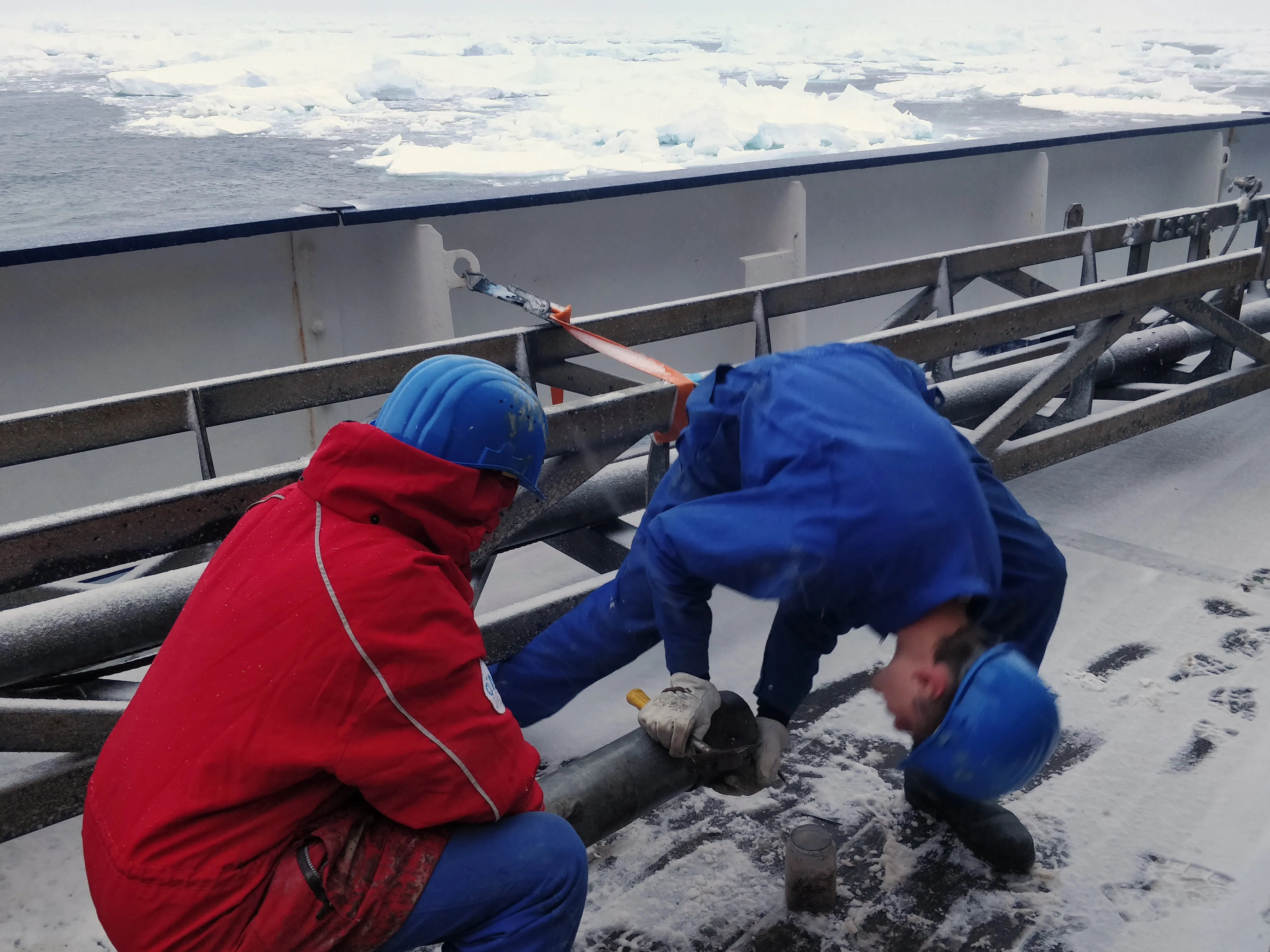

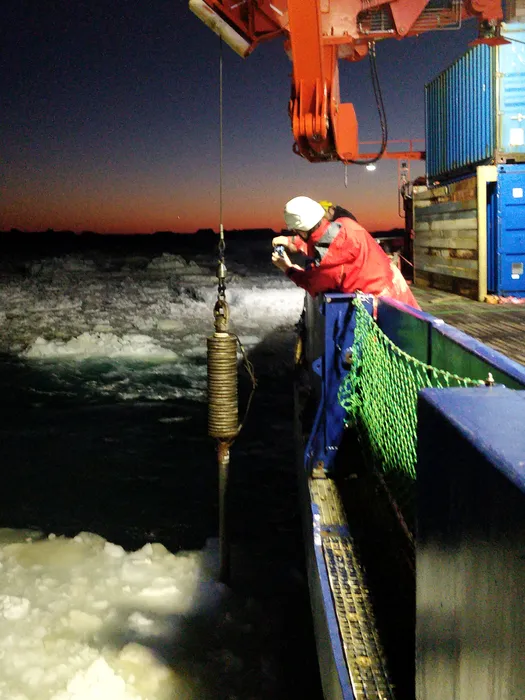

So once we’ve got into our waterproof warm clothes and hard hats, we prepare the gravity corer by labelling the plastic liner tube that goes inside the steel barrels and attaching the barrels to the big weight. Then we chuck it overboard: the ship’s crew attach it to the winch wire and then move it overboard and start lowering (we can go back inside at this point). It’s lowered at about one metre per second, so for a water depth of 2 km, it takes about half an hour to go down and half an hour to get back. Once it reaches the seafloor, it just sinks vertically into the mud (hopefully). After up to a couple of hours of waiting for the return journey, we dress up warm again and pull the corer back on deck: mostly the job of the crew and technicians, using boathooks, the crane, and hand signals.

We get an idea straight away if it’s worked or not: the barrels (but not the weight) should be covered in mud, and water should pour out of the top when it’s laid down. It also shouldn’t be bent — that’s called getting a banana, and it’s caused by too long a barrel on too hard sediments. Luckily we’ve only had one so far (and it was the other shift).

Anyway, assuming all looks good, we scientists then swoop in: we pull the liner out of the core barrel and cut it with a pipe-cutter every one metre. We cut the sediments inside with a wire, like cheese at the deli counter. Then the end is capped and the section is spirited away inside into the wet lab. All of this is very muddy and often wet too, so we do as much as possible outside, and then the rest is inside, but still in the “wet lab”, which is allowed to get wet and muddy.

The final job is to clean the corer, using a very powerful fire hose which is actually quite fun, though even wetter than the other jobs. I seem to have ended up as the one most often cleaning the mud off everything. Once that’s done, if the gravity corer is going straight back out again, we load another liner, and chuck it overboard again. Sometimes we change the length of the barrel, by adding or removing one or two of the heavy steel core barrels to make the right length. This is very much the work of us “deck monkeys” — the youngest and strongest of us.

That’s the main work on deck. During all of that, Matt and I get a toothpick and take a tiny speck of mud from the bottom of each one-metre section and when we’ve got them all, we go back inside and smear the mud on a microscope slide and then check to see if there are any diatoms therein and whether we know the ages of them. The idea is then that if there are any distinctive ones, we can say how old the core we just took is. So far nothing interesting has come up: we tried to recover some very old sediments in the last working area, but Matt and I had to be the bearers of bad news to the rest of the team.

Other than that, when there’s no station work going on (e.g. while we’re in transit), we do basically what I’ve been doing in the lab in Southampton: scanning the sections, splitting the cylinders in half lengthways, writing a detailed description of the layers within, and taking samples from them. While the seismic team was working (shooting very loud airguns into the water), I was one of the volunteer marine mammal observers (a.k.a. whale watchers) and had two (cold) two-hour shifts per day. At no point did I see a whale — luckily (for the whales and for the seismic team who would have had to stop if we had), and unluckily (for us observers who wanted to see whales). We did usually see plenty of seals and penguins on the ice though.

So that’s a typical day “on station”: lasting for twelve hours and ending at 4 am. It’s quite hard work, and often cold and wet (today the wind chill on deck is -10°C), but we’ve got a good team, especially considering half of us have never done this before. And it looks like I’m only going to have to do about four weeks of it on this eight-week expedition, the rest spent in the sauna.