Arrival: sea ice, seals, and penguins

This is part of a series of letters I sent home during my first research expedition, on the German icebreaker Polarstern.

You can start at the beginning here.

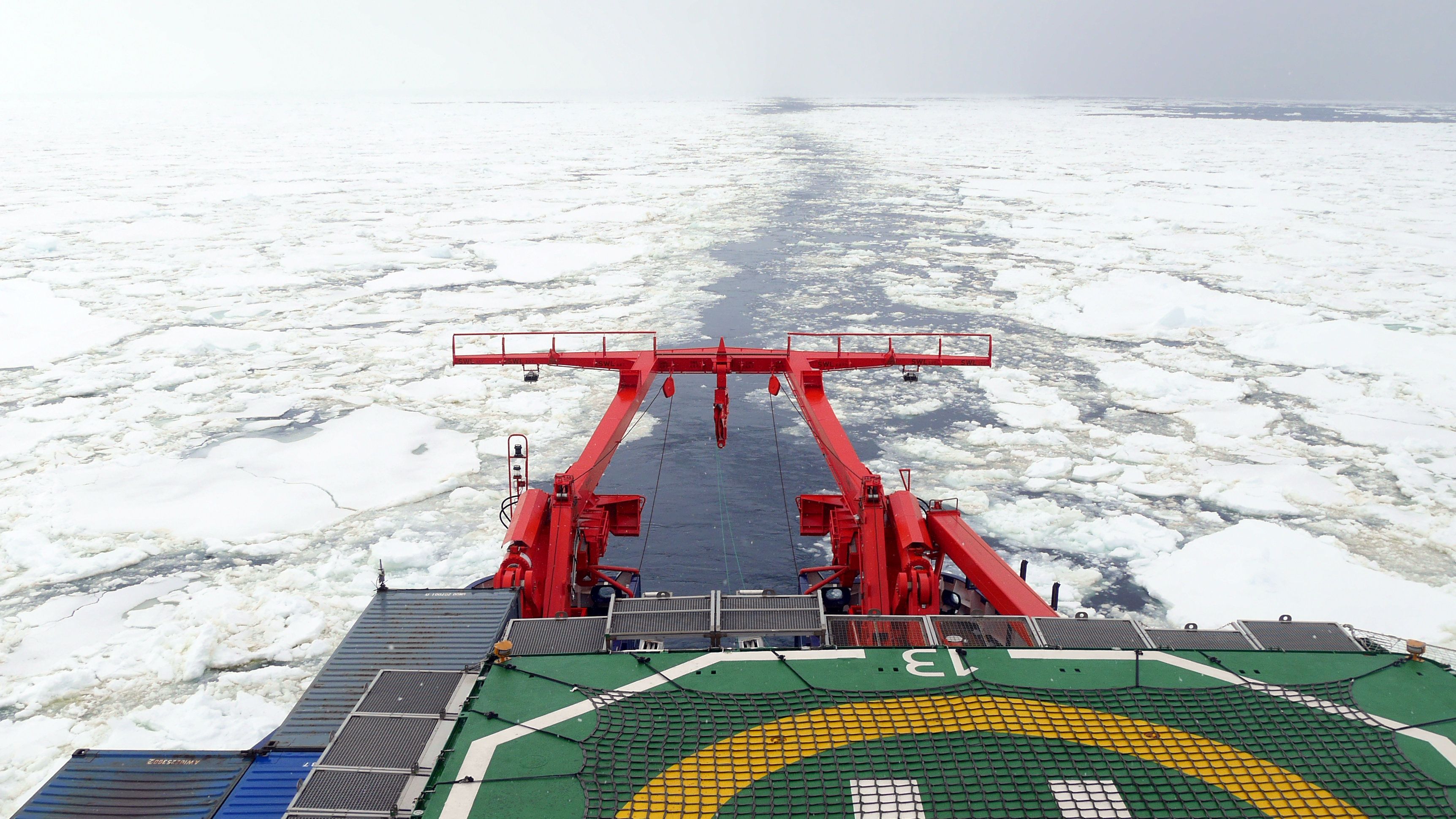

Since the last time I wrote, we’ve crossed both 60°S (the limits of the Antarctic Treaty System) and 66°S (the Antarctic Circle) — there’s no denying it now, we’re very much in Antarctica, especially since yesterday we spent most of the day ploughing through the pack ice. We started the day sighting some large tabular icebergs (remnants of the ice shelf, broken off and still about as tall as the ship). By lunchtime we were surrounded by lots of ice floes, but only about half of the surface covered in ice. Then by mid-afternoon, we were pushing through full coverage of densely packed ice floes. It was strangest in the middle part, where we were mostly sailing normally, but every now and then there’d be a large, solid ice floe in front of us, and we’d just keep going at full speed, straight at the ice. It would scrape and groan against the hull for a bit, break up, and be pushed out to the sides, and Polarstern would carry on as if nothing had happened.

When we were in the full pack ice though, we saw about four or five seals, a minke whale surfacing in a lead (open area of water), and about three or four groups of Adélie penguins. It was amazing to see real penguins in the wild, where they weren’t constrained by some concrete pen with a bit of water at the bottom, surrounded by gawking visitors. These were completely wild, and who knows, maybe we were the first humans they’d ever seen.

Strangely, though, we came out the other side of the pack ice, back to open water with a few growlers (small chunks of iceberg) around. I suppose the wind and waves had corralled the pack ice into a band which we just passed through. I’m sure we’ll find plenty more soon enough.

It struck me that the pack ice would be completely indistinguishable from the pack ice of Shackleton’s time. Of course, that was only a hundred or so years ago, but virtually nowhere on land has survived in exactly the same state for hundreds of years. Even the national parks have electricity pylons where there were none, or four-lane A-roads where there used to just be a muddy track. If you put Shackleton in my shoes, he’d recognise everything except the ship, which of course is infinitely more capable than his HMS Endurance (luckily for me). That the men of the Golden Age of exploration came here in ships a third of the size of Polarstern and powered by sail and piddling little engines one-fiftieth the power of Polarstern’s is incredible.

I’ve found my sea legs and now have no problems with the pitching and rolling of the ship, even for hours writing without a window nearby. I haven’t had to take any seasickness pills for days now, and I feel like I’ve passed an initiation of sorts. It also means I can fully take part in the extensive drinking on board… The day before yesterday was a “Zillertal” night — that being the name of the “pub” on board. Everything is 50 cents, though you can’t complain if you get a beer which is literally half foam. There’s also a strict rule banning photos — there are stories from one Zillertal evening way back when where a crew member saw a scientist taking a photo and threw the camera overboard. I don’t know if it was true, or just a story told to scare the rest of us into not taking any photos. The idea, I think, is that this is their time off, and they don’t want any record of it getting back to their employers, the shipping company. So far, I haven’t seen anything particularly incriminating though.

The last Zillertal was held to celebrate one of the scientists’ 60th birthday. He manned the bar and bought everyone’s drinks all evening, which even at 50 cents each must have cost him quite a lot. Naturally, we all made liberal use of this free bar, and most of us headed to bed at about 1:30. The late night actually worked out quite nicely as I’m now on the “night” shift, which starts at 4 pm and runs until 4 am. South of the Antarctic Circle is the best place in the world to be on the night shift though, because it’s completely light throughout the night. The only difficulty is the meals: for some reason, there is no recognition from the galley that people are on shifts, so I’m missing some meals and today I had a three-course Sunday lunch for breakfast.

I was on shift as we reached our first working area when we left the pack ice yesterday, and so I helped the geophysics team install some new modules on their streamer (a 600m long cable towed behind the ship, used for seismic surveys). It wasn’t difficult stuff, we just had to support the cable as it was unwound from its storage drum and streamed off the stern. Passing the cable hand-over-hand for 600 metres though was quite tough on the arms, so I was glad we weren’t needed to help pull it back in. I was happy to have any work to do though, having spent all of January so far doing not much in particular, first in quarantine and then in transit.

Today the other shift had the honour of recovering the first sediments (on a second try after the first corer came up empty), but I’ll get my go in a few hours. My shift this evening will also be interrupted by a barbeque on deck to say goodbye to our overwinterers, who will leave tomorrow for the Neumayer station and stay there for fifteen months through the Antarctic winter. We listened to a talk from a scientist on the cruise who coincidentally overwintered at the old Neumayer station 32 years ago. Absolutely crazy — that station was 9m underground when she went, and got deeper every year as snow fell on it. At least the modern station is on stilts above the ice. But the nine people on board are I think braver than astronauts on the ISS because the chance of outside assistance is so slim. On the ISS there’s a return capsule docked at all times, and you can be back on Earth surrounded by rescuers within hours if something went wrong. Overwintering at an Antarctic station, you’re very much alone. It’s taken us ten days to get here, and while you can fly to some places in Antarctica, you can’t when there’s a winter storm howling away outside.

Anyway, I’m glad I’m not doing that, and I’m looking forward to seeing the actual continent in the next few days.