Embarking on an Antarctic expedition

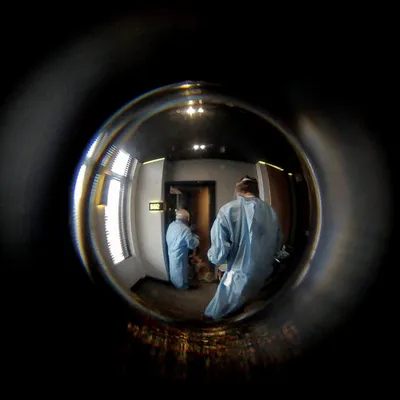

As part of my PhD, I was lucky enough to be invited to participate in a scientific research expedition organised by the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) to the East Antarctic margin, aboard the German research icebreaker Polarstern. PS128 took place in January and February 2022 (southern hemisphere summer), in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic and all the precautions that required.

Quite a few people back at home were interested to hear how it went, but communications at the bottom of the world are difficult, and at times all we could do was send plain text emails. So I started to do that, and in the end sent eight of them, about one per week. Here’s the first, with added photos taken at the time.

I finally made it on board! My quarantine is over, and I can breathe fresh air again, talk to other people, and go outside. A lot of family and friends were very careful about limiting socialising in the run-up to Christmas, and it was all worth it — the AWI doctors found no covid in our group through the whole 10 days of quarantine.

As I write, I’m in the South Atlantic Ocean, accompanied by humpback whales (confirmed by our onboard Marine Mammal Observers), Antarctic fulmars (identified by an ornithologically-inclined Danish geologist) and a large number of Germans. No penguins yet, but it’s rumoured that unlike large swathes of the East Antarctic margin, where we’re going there are a number of sizeable penguin colonies! Fingers crossed we see them, and not from too far away.

I’m beginning to settle in to my new ever-moving home: at first, anywhere with little or no view of the horizon was very questionable. Now, two days and many seasickness tablets in, I’m largely able to go where I want, if I don’t mind a slight queasiness. I’m far from the worst-affected on board — I haven’t yet thrown up at all, and haven’t had to consult the ship’s doctor. People are affected because it really is quite lumpy. I’m sure this is nothing — it was a force 6 (“strong breeze”; a hurricane is force 12) so it could get a lot worse (and I probably shouldn’t tempt fate). Icebreakers in general do, I think, tend to wallow a bit in reasonable swells on account of their blunt bows, designed for crushing ice not slicing through waves.

One of the places I don’t tend to fare so well seasickness-wise is my cabin, which has two scuttles but not a particularly expansive view of the horizon. I’m sharing with Matt, the other micropalaeontologist on board, and a Frenchman the same age as me. He laments the lack of wine with meals (his last cruise was on the Marion Dufrense, on which they serve wine with lunch and dinner, and apéritifs are taken before dinner), but he’s very contented with the food (as am I), and he’s generally a likeable, extroverted, guy.

Sleeping is lovely: the ship’s movement gently rocks you to sleep with no queasiness once your eyes are closed. Our bunks are really rather comfortable. The mattress is soft (and long enough!) and the bedding is clean and soft. We have curtains we can draw around us for a sliver of privacy, but otherwise it is rather cramped in here, not at all helped by the fact there are three of us in a two-person cabin: one of the oceanographers was not assigned a cabin and now has to bunk up with us on our bench. He doesn’t have nice curtains, nor the piece of wood under the mattress which we can wedge down the side of the bed to keep us in during very stormy weather, but he’s coping very well with the situation. His presence is due to a logistical compromise in delivering the over-winterers (those mad people staying fifteen months in the eternal Antarctic night); our cruise is therefore, for the first two weeks or so, over-subscribed.

This addition to our already small cabin has created a comedically cramped situation. Our third wheel removed the back from the bench to give his bed more width, and it now lies next to his ersatz bed, taking up valuable floor space. It also blocks access to one of the drawers under my bed, one of only three that actually open (the others are locked for some reason). We’re required to store our bulky lifejackets somewhere accessible in our cabin, so that removes another shelf, and we all have two large bags each — we have, after all, all packed for a two-month polar expedition. We are therefore quite literally living on top of each other, and I’m hugely relieved that neither of them snore or smell.

While we’re in transit to Neumeyer Station, we scientists don’t have much to do. This morning we started to unpack supplies and set up the labs, which involved getting into overalls and steel toe-capped shoes and using a pallet jack to move boxes out of shipping containers and into the labs. My black British Antarctic Survey overalls were a surprise hit, with several people at dinner confessing their jealousy of the black in a sea of red (crew) and blue (AWI scientists).

Other than that, we’re pretty much tourists on a rather cramped cruise for now. Meal times are perhaps the most regulated part of the day: policed by the head stewardess, there are a multitude of unwritten but very much spoken rules. The first, and most important, is that no scientist may sit at the captain’s table (identified by it being the first table on the left). The second rule is no workwear; the third rule is when you’ve finished your main course, move — anywhere — take your dessert with you, and the fourth is always obey timings: Breakfast is 07:30‒08:30. Lunch is 11:30‒12:30. Dinner is 17:30‒18:30. If you arrive too early, or too late to finish your meal by the end time, you will be told. And the last rule is to clear up after yourself. I have seen people reprimanded for breaching each one of these rules, but it’s more information than a personal attack. We all eat together (as many as can fit in the smallish mess), with the ship’s officers (on the famous captain’s table). The ship’s crew eat in the other mess, which is also the location of the fabled “Zillertal” pub on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. I’ll write about them when we have one.

Otherwise, we are at liberty to go wherever and do whatever we like. With a few limited exceptions, nowhere is off-limits to us. I’ve been whale-watching and horizon-watching on top of the bridge, at the stern, and on the heli-deck. There is also a gym (with treadmills and an erg), and a swimming pool and sauna, the former with basketball hoops at either end. It’s empty at the moment, so it looks more like a blue basketball court with a drain in the middle than a swimming pool.

We are now 250 nautical miles southeast of the Cape of Good Hope, with 2000 NM to go until we get to Neumeyer Station (or rather the Ekström Ice Shelf edge). I’ll send another update in a bit!